Artist and Expatriate: Elizabeth Rivers, 1903 – 1964

Written by Miriam O'Neal

Published on June 1, 2025.

Return to the contents page.

|

Elizabeth, or Betty, was the sister of Thomas Hall Rivers, the last Thomas in the great succession of family directors of the Rivers Nursery, and the father of Nigel and Tups. She was born in Little Pennys. She would have had around her the art of her aunt, May Rivers, whose watercolour paintings served to identify new fruit cultivars being developed in the Nursery in the extensive glasshouses and growing grounds that surrounded her home. May had a studio and refined some of her beautiful fruit images for inclusion in The Fruit Growers’ Guide by John Wright, 1892. Elizabeth may have seen other non-horticultural art May might have painted in her studio but which is not known now. After Elizabeth began to study art, initially at Goldsmiths in London, she soon left home to travel to Paris and then to live and paint initially in Aran and finally in Dublin for the rest of her life. Her work is very different from the exact but gleaming reality of May’s plums, as hers was in the modernist style of her own times. Elizabeth produced knottier images of a far harsher landscape and more rugged faces than found in the serene scenes of Sawbridgeworth.

In her lifetime her work attracted considerable attention - she exhibited and published volumes of prints and a book about her life in Ireland, A Stranger in Aran. At present her art is being explored once again and valued. We know of two studies of her life and work that are in preparation: one by Mary Ryan in Dublin and another by Miriam O’Neal writing in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

(See the useful background discussion in the Dictionary of Irish Biography.)

Miriam has written the thoughtful, well researched article below, giving us a sense of the intense, intimate art Elizabeth Rivers produced.

I discovered Elizabeth Joyce Rivers by accident, back in March 2020. As I sifted through the papers belonging to another long-time resident of Inis Mor, a sketch of an aged, gaunt-faced man with a dark-eyed gaze caught my eye. In the lower right corner, I could make out the signature, “E. Rivers.” Over the next five years, I came to know that signature and those quick, confident strokes of pencil and brush well. My discovery was by chance. I was on Aran for a different reason entirely. But it seems a fitting way to have started what would become a deep dive into the life of this stranger in Aran, since, she was, herself, only intending to spend a few weeks on Aran on a painting holiday. Neither of us expected what would happen next. She would find a home and I would discover a subject I had never imagined as my own.

Having arrived on the island on a short holiday in 1935, it would be 1943 before Rivers gave up her island home. The first show of Elizabeth Rivers’ “Aran” work was in the spring of 1936 at Daniel Egan’s Gallery in Dublin. It was a commercial and critical success that established her reputation in the Irish Modern art scene, in large part because of the technical skill on display, but also because viewers responded to the immediacy and intimacy of the work. Aran and its community were clearly both muse and familiar for the artist who had been told just a year earlier that she needed to “find [her] subject.” Her style was Modernist [1], but her subject matter was the spaces and people around her.

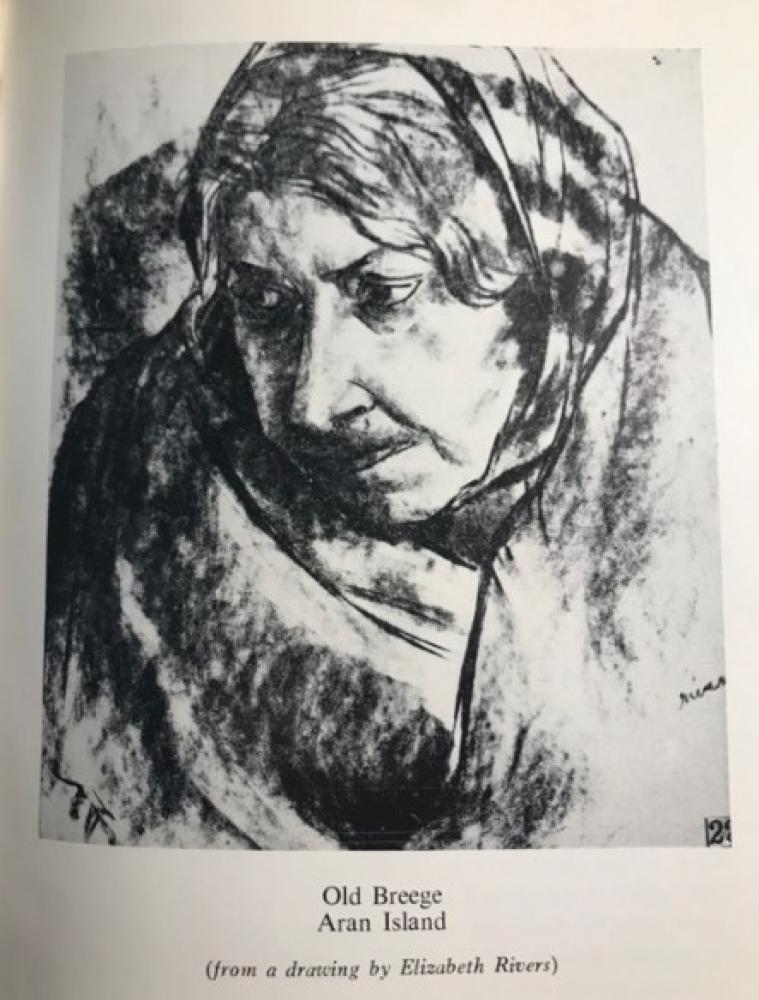

Four pieces from or inspired by Rivers’ Aran sojourn give us a sense of how much the island inspired her. When Daniel Egan’s Gallery in Dublin hosted the first show of Rivers’ Aran work, the islands came alive on paper. There were pencil drawings like “Throwing Up the Turf” and “Clearing the Nets” capturing a sense of her neighbours’ daily life. Her chalk drawings were of friends who often sat at her hearth. In fact her image of “Breege,” made in 1936, was included in Clara Rogers Vyvan’s memoir about her time in Ireland, On Timeless Shores in which her verbal description of Breege gives us the same character we see in chalk, in exacting detail. [2]

|

| Figure 1: “Old Breege” [3] |

A sketch that has become iconic in Rivers’ opus is her sketch of the “Man and Horse,” included in her 1946 Cuala Press book, Stranger in Aran. The spare lines connecting man and animal imbue a sense of the trust each has for the other, their heads close, the man’s hand resting on his horse’s mane. The models for the sketch were, most likely, her close friend, Pat Mullen and his horse, Silver Mane, who, together, trundled visitors from the quay at Kilronan, to the door of Man of Aran Cottage in Mullen’s sidecar. Not only does this simple sketch appear in Rivers’ book, the National Library of Ireland decided to include it in a wall sized collage of Elizabeth Rivers’ sketches and wood engravings that covers two walls of a small conference room at the NLI in Dublin.

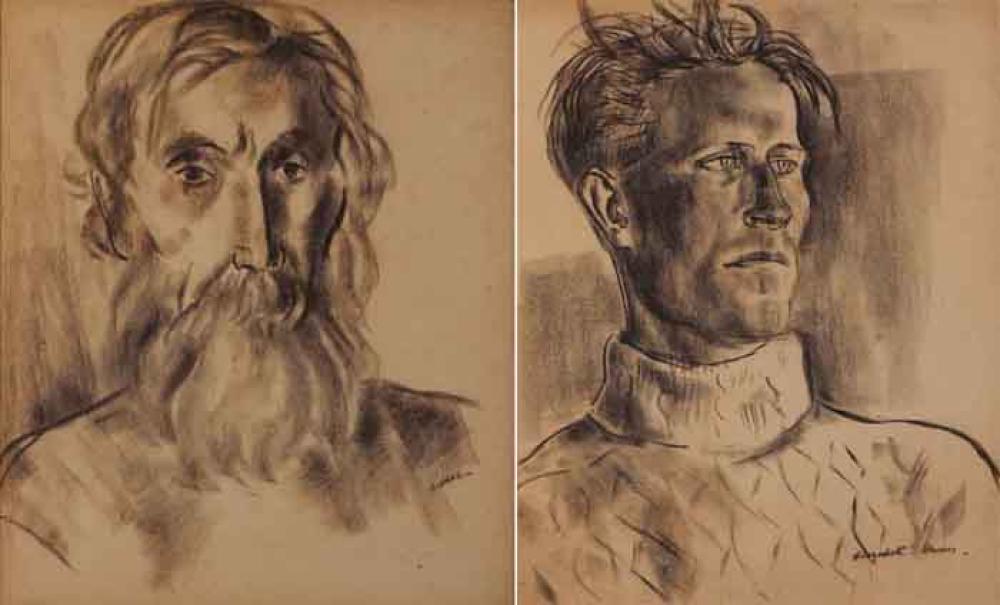

Her dyptich, “Old Man of Aran and Young Man of Aran” is a great example of how she worked in conte crayon, with shading and lines that draw the viewer to each man’s eyes. While the Old Man looks directly at us, with dark, shaded eyes, the Young Man’s clear eyes gaze at something in the distance. The former has the deep furrow and sharp face of a person who has earned his lines. Still, he looks like a person who is at one with his place. The latter’s rugged, but unlined face suggests his world is still forming and dreams are afoot. The pair of portraits most recently sold at auction in 2005 for €3400.

|

| Figure 2: “Old Man of Aran and Young Man of Aran” conte crayon on paper, c. 1935-1946 [4] |

Years after Elizabeth Rivers had left Aran and settled in Dublin, the colors, lines, and gestures of her Aran work would continue to inflect her work. Her ‘Aran Landscape’ c. 1955, is modernist in style, but representational as well. Aran’s animal world is caught in action as a cow, bound for market and in full gallop along the strand passes a startled horse while a woman in traditional Aran dress, watches the scene from above beside her panniered donkey.

|

| Figure 3: “Aran Landscape” Oil on board, c. 1955 [5] |

Rivers’ Aran palette includes familiar variations of pale blue sky and bluer sea, punctuated, here, by swaths of the cow’s red hide and the woman’s skirt. She describes this scene in Stranger of Aran, when, during a visit to the middle island, Inisheer, a cow being led to the shore for transport to Galway, escaped its halter and a few moments of chaos ensued.

Rivers' technique of containing parts of the image within thick black outlines, is reminiscent of her first instructor in Paris, Cubist artist, Andre Lhote, but also intones the direction she was headed in, as she worked with stained glass artist, Evie Hone, cartooning (drawing to full scale) the images that would rely on leading to connect the parts.

|

| Figure 4: Seabird on the Shore, 1962 [6] |

In the last years of her life, though she travelled through Italy and France, visiting museums and churches that housed some of her favorite early European painters, Rivers often still turned to her Aran palette and subject matter.

Here we see the same colors as in her “Aran Landscape,” though this time, the grays and blues fill the field and the reds work as a kind of punctuation point. The bit of kelp at the bird’s feet draws the eye and suggests a shoreline without building it out, allowing the shore bird to remain the focus. The black outlines of her earlier work are replaced by more solid colors and narrow lines, in particular the slim eye line and bit of dark tail and wing feathers.

Elizabeth Rivers was not the first Rivers woman to take up the brush. Her paternal aunt, May Rivers led the way at the turn of the 20th Century, studying in Paris and returning home with the idea of pursuing a career in the arts. However, it appears that her father, and Victorian society in general had other ideas for how a young woman from a well-known family in Sawbridgeworth should spend her time. Though she did produce dozens of landscapes, portraits, and still life paintings in her studio, her detailed botanical illustrations were what made it into the public realm. As the Rivers Nursery’s fruit tree and rose varieties grew more and more popular their catalogue became more and more expansive. May Rivers was charged with providing detailed illustrations of the various plants on offer, including their branch and leaf patterns, stems, blooms, etc. For the apple, pear, and plum trees, she would also include drawings of the fruits at various stages of ripeness. Her father allowed her to produce the same precise, informative illustrations for a few other nurseries as well, though presumably of produce not in competition with the Rivers Nursery. Unfortunately for those interested in seeing more of May Rivers’ work, much of it was destroyed in a fire at the facility where May’s work was stored along with many other Rivers artifacts. A few pieces remain in the possession of her descendants. [7]

The only image we know of that shows us May Rivers’ non-botanical artwork is a photograph that her niece, managed to preserve through myriad changes of household, including moves from Sawbridgeworth to Paris to London, and eventually to the Aran Islands. Perhaps it was a talisman for Elizabeth; a reminder to keep picking up her pencil or brush.

More than sixty years after her death, Elizabeth Rivers, the British artist who went on a painting holiday to Aran and made it her home, maintains her place in modern art. As Art Historians revisit and deepen their understanding of, most especially, the role of women in Irish Modernist art, that place seems secure.

Endnotes and Bibliography

Clink on the reference numbers to return to the place in the text.

[1] - Modernist Art was a late 19th Century and early 20th Century movement in which visual artists

moved away used more experimental approaches to capture the essence of their subject matter. Cubism,

Impressionism, Abstraction, and other styles that were not purely representational would be considered

Modernist. In Rivers’ case, we can see that she often used outline, a limited palette, and minimalist

forms that brought energy to the subject rather than simply recreating it in two dimensions.

[2] - “…old Breege sat in silence, her shawl drawn closely about her face, both hands twitching on her knees; her

fading eyes [ ] peered at you with a strange light behind them, as if she were seeing beyond your face into your

very soul…” Vyvyan, Clara Rogers, On Timeless Shores, “Peter Owen Limited, London, SW7, MCMLVII. P.151

[3] - Rivers, Elizabeth, “Old Breege”, Chalk drawing, first shown in 1936 at Daniel Egan’s Gallery, Dublin,

reproduced in Clara Rogers Vyvyan’s, On Timeless Shores, P.127 (author’s photograph).

[4] - Rivers, Elizabeth, “Old Man of Aran and Young Man of Aran”, Image retrieved from Whyte’s Auction Page, 4

April 2026 (https://www.whytes.ie/art/old-man-aran-islands-and-young-man-aran-islands-a-pair/123707/)

[5] - Rivers, Elizabeth, “Aran Landscape”, C. 1955. IMMA Collection. Image retrieved 4 April 2025,

(https://imma.ie/collection/aran-landscape/)

[6] - Rivers, Elizabeth, “Seabird on the Shore”, 1962. IMMA Collection. Image retrieved 4 April 2025.

(https://imma.ie/collection/seabird-on-the-shore-1962/)

[7] - Author’s personal correspondence with Rivers descendants, 14 February 2024.

Miriam O'Neil - May 2025

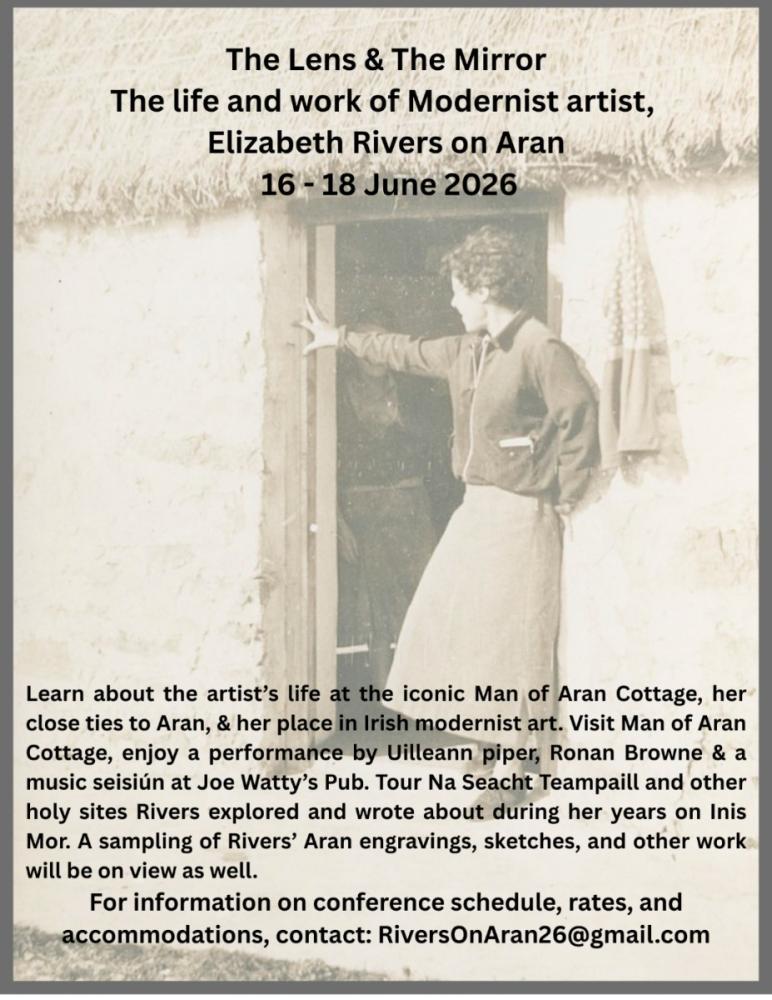

Miriam O'Neal lives and writes in Plymouth, Massachusetts where she is the 2024-2026 Plymouth Poet Laureate. A member of the American Academy of Poets and the National Book Critics Circle, she has published three collections of poetry as well as poems and book reviews in numerous journals, including The Galway Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, North Dakota Quarterly, and Lily Poetry Review. She is currently at work on the first full length biography on Elizabeth Rivers. The Lens & The Mirror: The Life & Work of Elizabeth Rivers, which gives special attention to how her Aran years as the inflection point in her career.

Miriam O'Neal will be hosting a conference on Elizabeth Rivers Life on Aran. E-mail RiversOnAran26@gmail.com for further details.

|

Return to the contents page.